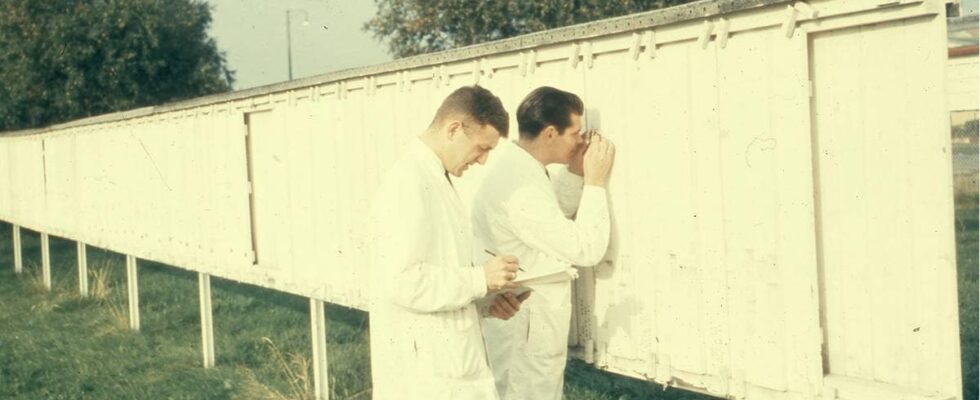

On 21 June 2024, the new science museum opens in Jøssingfjord in Rogaland. The premiere exhibition has already caused an uproar internationally, even before the museum has opened its doors to the public. It shows a scientific research project about how the country of Norway has made the whole world whiter. Read the last one again: … how the country of Norway has made the whole world whiter … Huh? Is Norway to blame for so much of the world being white? To understand this story, you must first get to know what it’s all about, namely the Norwegian invention titanium white. Advertising poster for titanium white from approx. 1920. Photo: Østfoldmuseen’s archive All the white things you see around you every day Titanium white, or titanium dioxide as the product is called, is a completely white powder that is used as a dye in almost all the white things you have around you. You find it in paint, toothpaste, plastic chairs, clothes, cosmetics, varnish, sunscreen, paper, dentures, rubber, plastic bags, glass, in pills you get from the doctor – in short, everything that is colored white, with the exception of food; it was banned in the EU in 2022. How Norway made the world whiter “How Norway Made the World Whiter” is a five-year scientific research project at the University of Bergen. The Research Council of Norway has given NOK 12 million to the project and the Program for Artistic Development Work has given NOK 3 million more the project. Those responsible are art historian Ingrid Halland and artist Marte Johnslien. In “How Norway Made the World Whiter”, the researchers want to study what consequences the production of titanium dioxide has had for modernism (culturally), for the environment (nature), and as an aesthetic idea. Parts of this project are based on artistic works. Before this, even fish balls were colored with titanium white (stated as E171 on the product). The world’s consumption of this dye is enormous. And the commercials that were made for the product titanium white are very entertaining (I recommend playing it here): Advertisement for titanium white from 1956. The Norwegian origin of the color white When professor of chemistry Peder Farup and industrial leader Gustav Jebsen received a patent for the dye titanium white in 1909, It was a sensation. Peder Farup on the left and Gustav Jebsen on the right Photo: HILFING RASMUSSEN / NTNU UNIVERSITY LIBRARY and OSLO MUSEUM – Titan white solved all the previous problems with existing white colours, says Ingrid Halland, one of the two researchers behind the project “How Norway Made the World Whiter”. Ingrid Halland Photo: Solveig Tjetland In 1909 it had been discovered that white lead was toxic and it was therefore banned. The other white color that was available, zinc white, was known to have very poor coverage. Durability tests on paint after 3.5 years – zinc white versus titanium white. The result is obvious: Titanium white keeps the white color much better. Photo: Østfoldmuseen’s archive Titanium white, on the other hand, was neither transparent nor toxic and with Farup and Jebsen’s invention, enormous quantities of the substance could be produced. – Titanium white has meant a lot to modern design, says Ingrid Halland. With the invention of titanium white, absolutely everything could be dyed the whitest white – from southern towns to Apple products, to name a few. Risør with its white wooden houses and the guest harbor filled with boats in the summer of 2020. The town is often called “the white town by the Skagerak”. Photo: Erik Johansen / NTB The color white has become increasingly prominent with modern design and with functionalism’s demands for clean shapes and surfaces. It comes from here At Jøssingfjorden in Rogaland is the world’s largest deposit of titanium ironstone. The Titan mine in Jøssingfjord. Until 1994, the sludge was thrown into the fjord. When the emissions ended, the fjord had been filled up from 70 to 20 meters deep. Landfill is now used, but it will also soon be full. Photo: Mike Norton / wikimedia commons The two inventors of the dye knew this. That is why they founded the company Titania A/S with a mine in Jøssingfjord and further processing in Fredrikstad in 1916. This is how titanium white is produced Photo: Solveig Sørensen / NGU Production of titanium white starts with a black mineral called ilmenite. The black powder in the picture above is crushed ilmenite (titanium iron oxide). The white is titanium dioxide, from which the iron has been removed. The raw material is found in Jøssingfjord in Rogaland, but is further processed in Fredrikstad. There, the ilmenite is crushed into a fine powder. Titanium dioxide can then be separated out, and the result is a pigment that is the whitest white. World production of titanium dioxide pigment was around 10 million tonnes in 2016. This has caused such major pollution problems that the EU has a separate titanium dioxide directive (92/112/EEC). In 1927 the company was bought by American interests. The entire enterprise with mine and factory is today owned by the mining company Kronos Worldwide. Every day, 400 tonnes of titanium dioxide are produced. It takes 14 days to refine the product, and Norway is still one of the world’s largest suppliers. It is true that the country of Norway has made the world whiter. But why is the color so popular? Advertisement for white paint from the 1920s. Photo: Østfoldmuseen’s archive The desire for white The obvious answer is the search for light. But cultural history can also say something about our relationship with the color white. Angels are white. The Pope’s textiles too. In addition, many magnificent buildings are completely white. BEAUTIFUL BUILDING: The National Museum in Brasilia – designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer. Photo: RICARDO MORAES / Reuters The whitest white used to be associated with something very special. With the invention of titanium white, everyone could get as much white as they wanted. And people want white objects. It feels so clean. But it is also an aesthetic product that puts a heavy burden on the environment. Jøssingfjorden 25 August 1983: The Titania demonstration in Jøssingfjorden. Frederic Hauge in Bellona shows the victory sign. It was a year-long battle to force land disposal for mine sludge. Photo: NTB Landscapes are destroyed, and enormous amounts of mine sludge have to be deposited. This is also part of the story of Norwegian titanium white that the two researchers Halland and Johnslien want to highlight through their work. But then a certain waste ombudsman came into play. Facsimile: Nettavisen Sløseri or not? The waste ombudsman is Are Søberg’s title for himself. Under this tab, Søberg looks for publicly funded projects that he perceives as a wasteful use of the community’s funds. When Søberg has found such a project, volleys of grenades are fired on social media. In 2023, he was tipped off about the project “How Norway Made the World Whiter”. There he read a job advertisement for a senior researcher which stated the following: “The project examines how a Norwegian innovation – the industrial production of the white pigment titanium dioxide – not only led to an aesthetic desire for white surfaces, but which was also associated with racist attitudes.” That caused the alarm to go off for the waste ombudsman. He thundered against the project. To Nettavisen (where he also works as a commentator) he said the following: – It seems completely idiotic. I thought this would have been an exceptionally funny joke if I had been creative enough. It comes across as satire. Ingrid Halland does not know how the international media got hold of what the waste ombudsman had said about the research project. But the result was at least that the project was denounced as woke idiocy around the world. The inbox overflowed with unpleasant messages from the public, based on these posts. – No international media called to ask about the case either, says Ingrid Halland. – They only printed what the waste ombudsman had said about us. – But it is you who write about the color white, that it is “connected with racist attitudes”. It is not something that the waste ombudsman came up with himself. – No, that is correct, answers Halland, but she clarifies that scientific work is always about breaking down a topic in detail for investigation. – The color white is not just one thing. We wanted to look at this industry from many sides. Why haven’t we heard about the color when titanium white is a dye that is sold for billions of kroner, and Norway is a major supplier worldwide? Why do modern people want so much to be white, and what does this production do to the landscape and environmental waste? Moreover – and now we get to the nitty-gritty of this matter – the color white itself is loaded with heavy symbolism. Racism? Here is an example of earlier marketing of Norwegian titanium white: Advertisement for titanium white in 1920. Photo: Østfoldmuseen’s archive Part of the project “How Norway Made the World Whiter” has been to catalog historical archives. Titanium white was early marketed with rose paint and Norwegian flags. But there were also advertisements with racist features. – The fact that we point this out was made a main point by the waste ombudsman, says Halland, – but it is only a small part of our research. When the new science museum in Jøssingfjord opens its doors on 21 June, it will be with the story of the local product titanium dioxide. Artist Maiken Stene installs the painting “Storgangen” as part of the exhibition Campaign! at Jøssingfjord Science Museum. Photo: Hanna Biørnstad The museum will house both a permanent exhibition about the local product, as well as a special exhibition based on the research project. And at Velferden – Sokndal Stage for Contemporary Art – ceramicist Marte Johnslien and her master’s students from the Oslo School of the Arts will exhibit work, from 29 June. Will the Waste Ombudsman Are Søberg visit any of these exhibitions, do you think? Probably not. He tells news that he has not followed the project very closely in the past year, but he believes that it now appears to be something completely different from what he experienced that it was about from the start. – The fact that they now instead choose to look at the project as industrial history probably means that there is a slightly greater chance that something interesting can come out of it. Although I probably wouldn’t spend many millions of tax kroner anyway for a group to talk about the history of a paint factory for six years. Whatever you think about this – one thing is certain: the whitest white is still as popular both in toothpaste and as a house colour. And now you at least know where the color comes from. SOURCES: Hi, if you have input on the matter, or suggestions for other things I should write about, then send me an email. And if you have just read about the falling price of diamonds, then you can read my story “A declining superstar” about why this happens.

ttn-69

Norwegian white color characterizes the whole world – Culture