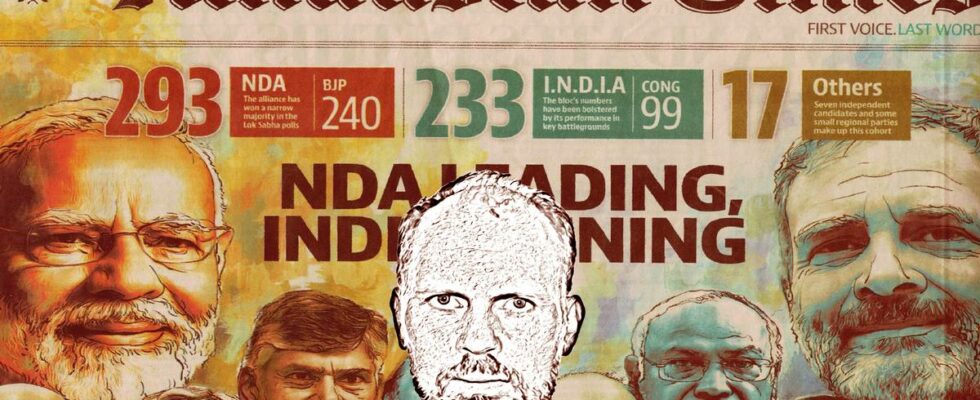

Many of us have more than once in our lives stood with our heads down in the bin looking for a mitten or hat at school for one of the children. It was a bit like that to be back in India for the first time in nine years. Not that there was a mitten or hat I needed in temperatures of 46 to over 49 degrees. What I was looking for was the stuff India was made of. The India I once knew. At least a little way into the complex fabric of culture, religion, caste and politics. People are gathered for a Puja or Hindu prayer on the banks of the Ganges. Photo: Philip Lote / news People and robbers in rural India belong to the journalistic youth for me. In the 90s, I traveled and freelanced across rural and urban areas. Long before any mobile network was developed, we hunted for telephone booths with ISDN lines, satellite lines. Sitting on stacks of pineapples in a market or at a tea stand at a crossroads, we called in news reports to news. It was a time with a freedom that you don’t get again later in life; where you don’t have to earn more than what the stay costs, and can then travel for a long time, as long as an Indian election lasts. Photographer Stig Jaarvik and I tracked down and found Phoolan Devi, the low-caste woman and bandit queen. In the same year, in 1996, she was elected to parliament for a party on the left. Phoolan Devi surrounded by party comrades on her way into parliament in 1997. Photo: AP Five years later, Phoolan Devi was shot dead outside her home in Delhi. Then we could reuse one of the few interviews she ever gave to foreign journalists. I tell you about this because the bloodstains on the pavement outside Phoolan Devi’s house in New Delhi are one of many testimonies to the contradictions between high and low caste, Hindus and Muslims. Authorities in 2001 point to the blood where Phoolan Devi was shot outside her own home in Delhi. Photo: AP Hate speech, division and violence are not something that came to Indian politics when Narendra Modi became prime minister and the Hindu nationalists won a clear majority, securing their grip on power 10 years ago. One insider a second When I landed in New Delhi late in May, it still felt like something was different. Not just a little different, but completely changed. It was a few days before the last election day in the biggest election the world has ever seen. It wasn’t so much about the physical sizes. India is today the world’s most populous country. If you go to the population clock on Worldometer, you will see that the population is increasing by one new Indian resident every second. In China, on the other hand, the population is decreasing by approximately one inhabitant per minute. Both are just over 1.4 billion. It is estimated that there are 16 million more Indians than Chinese in the world. India has a young population. The economy is growing rapidly at a time when other economies are in danger of shrinking. The country attracts factories and investments from iPhone, Samsung and others. They have entered into a trade agreement with Norway, while other countries have followed suit to obtain their corresponding agreements. India is played strong by the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea as a counterweight to China, both economically, politically and militarily. Last year, India became the first nation to land a vehicle on the moon’s south pole. Impressive, but it is not unexpected that India is in a place reminiscent of where China was about 20 years ago. That they make some great progress. Modi’s PR machine An India with ambitions is not new. What I didn’t recognize was something far more unpleasant. The last time I was in the country was in 2015. Modi had ruled for a year. Even then, Indian journalists said that Modi had put up a glass wall between himself and the press corps. Modi did not meet journalists in the open. Didn’t answer questions. Instead, he addressed the people in a weekly radio address. He tweeted his messages. Chose platforms where he was not contradicted. By 2024, Modi and the BJP’s PR machine had evolved into something so well-oiled and super-professional that it seemed unbeatable. Prime Minister Narendra Modi arrives at BJP’s election vigil and celebration at party office in Delhi. Photo: Philip Lote / news In neighborhoods across the country, young Indians sat and reposted messages developed centrally at the party office of the BJP. They were shared on Facebook and in Whatsapp groups, but the messages were adapted to local languages and local politics where they were. India’s largest media house was bought by India’s richest business magnates, who nurtured close ties to Modi. From being balanced and critical of power, the media had moved to being for, or even more for, Modi. Did not dare to criticize Parts of the state apparatus also seemed rigged in favor of Modi. In March, shortly before the elections, the founder of the Aam Admi Party, the common man’s party, was arrested. Arvind Kejriwal is Delhi’s chief minister and the BJP’s staunchest opponent in the capital. The largest opposition party, the Congress Party, had its bank accounts frozen. In a meeting with young voters, a young man asked that we not use his full name. The reason was that he had thought to express himself critically about the government; about social differences and how Modi whipped up tension between Muslims and Hindus. The young man said that he had just secured a job as a teacher in the public school. He was afraid that he would never start the new job if he said what he meant by his full name. On the last election day, the newspapers printed articles that Modi had conducted a marathon of an election campaign. The opposition got little space. The election day polls all pointed in the direction of another clear victory for Modi and the BJP. The multi-party state of India, the world’s largest democracy, began to have some features that might resemble a one-party state, which I otherwise report a lot about. Out of the box of oblivion Then something happened. On Tuesday 4 June, at eight o’clock in the morning, the counting of votes began. Within a few hours, it became clear that the BJP and Modi would not win easily or overwhelmingly. Maybe they wouldn’t even get a majority on their own. The expert panels in the news channels’ studios changed abruptly. From the box of forgetfulness, the commentators brought out an India I recognized. – Never underestimate the Indian voter, exclaimed one commentator. – The BJP will have to go inside themselves and see what they have done wrong. The experts began to praise the opposition’s election campaign. The head of polling firm Axis India broke down in tears on live television because they had failed to pick up on the sentiments of the people. The head of Axis India, Pradeep Gupta in tears in the broadcast to India Today when he had to answer why the election day polls missed badly. Photo: Screenshot / India Today What were these currents? The answer is not simple. In our meetings with people in the run-up to the election, several said that they saw nothing of India’s economic growth, but instead that the prices of food, fuel and electricity had gone up. Opinion polls have the weakness that they do not easily capture what people think in their quiet minds. Perhaps many felt a sense of unease. Not sure how healthy it is for one party and one leader to secure too much power Perhaps Modi scared more people than he won when he stepped up his anti-Muslim rhetoric. The result was that the BJP was forced into a coalition with parties that do not share the BJP’s Hindu nationalist ideology. On June 5, the day after the count, there was balance on the front page of the Hindustan Times. NDA is the coalition of BJP. The opposition alliance had taken the name; INDIA Photo: Facsimile Hindustan Times / news It is to the BJP and the other major parties’ credit that no one has seriously claimed that the election was rigged. They have accepted the verdict of the voters. In the big global election year 2024, that is not something we can take for granted in all countries. Democracy itself was, in a sense, at an election in India. The voters and the respect for their vote brought Indian politics to a sort of ancient balance. Listen to Utenriksredaksjonen’s podcast: Published 15.06.2024, at 16.47

ttn-69

India lost and found – news Urix – Foreign news and documentaries