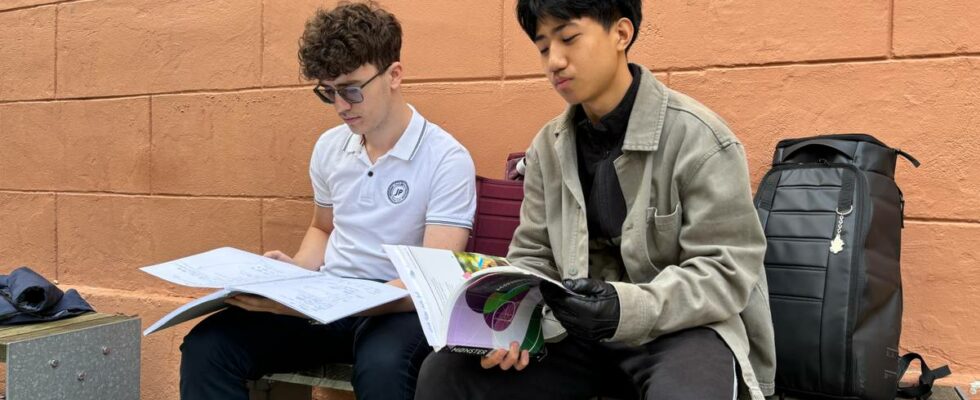

Dropping out of high school is a major risk factor. Young people who do not complete upper secondary education are seven times more likely to end up outside work and education than other peers. Nicolas Georg Andrej Rajala (18) came from Romania to Norway four years ago. The father had worked here for periods since 2011. – In fact, my dream was to be a bank manager. In any case, I want to work in finance, he says. Nicolas is in the group that most often drops out of upper secondary school – immigrant boys with a short stay in Norway. Immigration categories and education Immigrants are people who have immigrated to Norway themselves, who were born abroad to two foreign-born parents and have four foreign-born grandparents. There are 931,081 immigrants in Norway in 2024, that is 17 percent of the population. Norwegian-born with immigrant parents are people who were born in Norway and have two foreign parents and four foreign grandparents. There are 221,459 Norwegian-born with immigrant parents, 4 per cent of the population. Those who were five years or younger at the time of immigration have largely the same pattern as those without an immigrant background, with relatively equal proportions of completed university and college education. As a whole, men are over-represented in the lower levels of education, that is primary school and upper secondary level. Conversely, there are consistently more women than men who have a university and college education as their highest level of education. This applies to both immigrants and those without an immigrant background, in all cohorts. Sources: IMdi and SSB There are also large differences within this group. For example, students who come as a result of flight will have a lower completion rate in upper secondary school than students whose parents came as migrant workers. Much is going in the right direction The fact that many young immigrants drop out of upper secondary education is a major concern. – I think everyone feels that it is a challenge. It’s about health, it’s about outsiders, it’s about someone not feeling at home, says principal Karen Kristine Rasmussen at Bergen Cathedral School. At the same time, the statistics show that it is going in the right direction after all, Nicolas is surprised that the number is so high. – It is also a lost potential for Norway’s future, he believes. His friend John Mitchel came to Norway from the Philippines in 2021. His mother already had a job in Norway. He knows someone in first class who quit. – He found a job, wanted to start earning money early. I think he is growing up too soon, but there is no right answer to that, says John Mitchel Dagpin. Large gender differences Although four out of ten immigrant boys drop out of upper secondary school, the numbers are slowly increasing. And far more boys born in Norway to immigrant parents complete upper secondary education. – Outsiders and poverty go hand in hand. It is not only bad for those affected. It is also a major societal challenge. This is a task that must be solved jointly, says Libe Rieber-Mohn. Here from a conversation with Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre. Photo: Ksenia Novikova / news – If we see young immigrants as one, a relatively positive picture emerges. Today there are more people with an immigrant background who participate in work or education than before and the proportion who complete upper secondary education has increased, says Imdi director Libe Rieber-Mohn to news. – Despite the fact that many arrows point in the right direction, there are still some challenges, for example when it comes to gender differences, she adds. Girls take the lead Among girls born in Norway to immigrant parents, the proportion who completed upper secondary education was as high as in the rest of the population. Imdi sees some things that are repeated among students who drop out of school. – We know that those who drop out of school more often experience alienation and that to a greater extent they live in families with low incomes. Age at immigration has a big impact on how things go in school, says Rieber-Mohn. Among those who immigrated before school age, there are small differences compared to those who were born in Norway to immigrant parents. This applies to both girls and boys. – This emphasizes the importance of early intervention, targeted Norwegian education and measures that support both the young people and their families throughout the school year, says the Imdi director. The completion rate for preparatory education programs is markedly higher than for vocational subjects. – The challenge with low completion rates is often a combination of choosing a vocational subject that generally has a lower completion rate, and having a background in flight. There is a trend for well-resourced parents to have children who choose study preparation, while among resource-poor parents (of which refugees are often a part) it is a bit more mixed what the children choose, says Daniel Instebø in Statistics Norway. Many out of work and education Around two out of ten young immigrants are out of work, education or training. The proportion is more than twice as high as in the rest of the population. NB! Note that it is good here if the curve goes down. The proportion of young people outside work and education is lower in Norway than in other comparable countries. But if we look at the immigrant group, it is higher than countries we can compare ourselves to. Although the group has decreased slightly in the last ten years, and thus approached the general population, the gap is large. – Learning to become people Principal Karen Kristine Rasmussen at Bergen Cathedral School says they work a lot with the student environment and that the students must find their place. The school has students from many different cultures. – Pupils are not just at school to learn subjects. They are also here to learn to become people, says Rasmussen. HAS STUDENTS FROM MANY COUNTRIES: Principal Karen Kristine Rasmussen at Bergen Cathedral School. Photo: John Inge Johansen / news They have 13–14 student organisations. There is a knitting club, debating club, drawing club and volleyball team to name a few. – The students create them based on their interests. And then almost anyone is allowed to participate, she says. Motivated by the environment John Mitchel Dagpin (17) says his friends at school motivate him. John Mitchel Dagpin came to Norway in 2021. Photo: John Inge Johansen / news – The best thing about being at school? The people, of course, he smiles and elaborates: – There are many different people. Many wise people who have experienced a lot. And they know a lot too, different skills. So yes, the people are perhaps also a motivating factor for why people go to school, he believes. – What do you want to be? Do you have any dreams? – I don’t know that. That’s why I use the time to go to school, he replies. Published 15.10.2024, at 05.04

ttn-69

More people with an immigrant background complete upper secondary education – news Norway – Overview of news from different parts of the country